Discipline Basics

Often parents wonder how they can create an environment in their homes and in their relationships with their children that will nurture their children’s ability to meet the challenges they will confront as they grow and move out into the world. The kind of discipline you use can have a big influence on this.

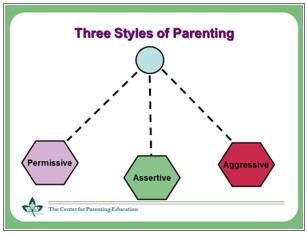

There are three main parenting styles that are most commonly used.

There are three main parenting styles that are most commonly used.

• What distinguishes one from the other is the amount and kind of structure that the family has in place and the kind of discipline it imposes.

• These different approaches exist on the arc of a pendulum from the loosest organization to the most rigid.

• Most families are blends of all three strategies, usually with one approach being dominant.

The Three Parenting Styles

These three styles are called the Permissive style, the Aggressive style, and the Assertive style.

Let’s take a look at three different ways a parent might handle the same situation: an eight-year-old leaves his things all over the family room floor even after being asked numerous times to pick up after himself.

Permissive Style

“Oh Honey, I see your stuff is still left out. I guess you were too busy to clean up. I’ll clean-up for you so you can find everything next time you want to play with them.”

This parent demonstrates what is called the Permissive style that relies most heavily on the nurture role, but without offering enough structure.

This parent does not hold the child accountable for cleaning up his items and does not show herself to be the authority figure in the home.

Clues that you are using the Permissive Style

• Evading discipline issues

• Begging for cooperation

• Acting flustered

• Being unclear or indirect in your requests

• Being a martyr versus asking for what you need

• Worrying about being “liked” by your child

• Fearing that you may upset your child

• Blaming yourself and taking all the responsibility when problems arise

• Being inconsistent with expectations

Results of Using the Permissive Style

• Your child does not learn to respect you.

• He is not held accountable for his behavior.

• Proper limits are not set.

• Your child has too much power in the house.

• He does not learn to be responsible to fulfill obligations.

• He is not encouraged to learn the tasks of everyday living that he will need as an adult.

As a result, your child will not build healthy self-esteem. It also damages the relationship between you and your child.

When you use a permissive style of parenting, you do not show yourself to be “in-charge,” and as a result, your child will be less likely to turn to you for guidance in other situations in his life.

Aggressive Style

“I’m sick and tired of seeing your things all over the room. Why are you such an irresponsible slob? That’s it for you – you are grounded for a week and I’m throwing out all your things.”

This parent demonstrates the other end of the discipline pendulum, which is called the Aggressive style of parenting. It relies most heavily on the structure role, while not including enough caring and nurture.

A parent using this style refuses to listen to the child’s point of view at all and is typically harsh, angry, and cold.

Clues that you are using the Aggressive Style

• Having many power struggles

• Accusing your child of having bad intentions

• Discrediting your child’s ideas

• Tricking, teasing, humiliating your child

• Doling out harsh punishments

• Rigidly enforcing rules

• Withholding information about expectations

• Having a litany of strict rules

Results of Using the Aggressive Style

• The self-esteem of your child is damaged because he does not feel understood or supported.

• The parent-child relationship is weakened as your child would not feel that you are someone he could turn to if he had a problem.

• Children from these families often become either overly submissive or rebellious.

Assertive Style

“Jon, I see your games are still not put away as I asked you to do. It is really bothering me that I can’t count on you to take care of your things and I can’t stand seeing the family room be such a mess. We need to come up with a plan for you to put your things away. Until we can agree upon a plan, there are no electronics for you.”

This parent demonstrates the third style of discipline which falls in between the two extremes and is called the Assertive approach to parenting.

Parents using this approach are willing to listen and yet still hold firm so that the parent’s and the child’s needs are both basically met.

When setting limits, the parent does not get sidetracked, can provide choices, and allows the child an opportunity to participate in finding a solution.

Clues that you are using the Assertive Style

• Persisting until your requests are followed

• Listening to your child’s point of view

• Giving brief reasons

• Revealing honest feelings

• Politely refusing

• Empathizing

• Setting reasonable consequences

• Accepting your need to be “in-charge”

• Not blaming your child

• Making clear, direct requests

• Having rules that are flexible

Results of Using the Assertive Style

This style:

• Is most successful because it uses a healthy balance of both nurture and structure.

• Raises your child’s self-esteem because you communicate that your child is lovable and loved and worthy of respect.

• Communicates that your child is capable of meeting the demands that life places on him – he can tolerate some frustration and he can contribute to solving the problems he encounters.

• Builds a strong parent-child relationship, as your child realizes that he can depend on you to both understand his struggles and provide guidance and support. When you use an Assertive style of parenting, your child is more likely to come to you for direction in the future as issues arise in his life.

Benefits to Children

They:

• See you as a source of support.

• Have a sense of safety because rules are in place.

• Feel lovable and worthy of being cared for.

• Feel listened to and understood.

• Develop basic feelings of trust in relationships.

• Learn to be kind to other people.

• Consider another person’s point of view.

• Learn to tolerate frustration and disappointment.

• Learn to be responsible and to make decisions.

• Learn that they are capable of doing things.

• Become more independent.

• Learn they can tackle difficult situations.

Tips for Using an Assertive Parenting Style

Your children see you modeling assertiveness as you take care of and respect yourself and others. To use an Assertive approach:

• LISTEN

When your children talk about things that may bother them, acknowledge their feelings and let them know you have heard them.

• Be respectful

When you discipline, you can set limits without blaming or shaming your children.

• Model

Exhibit the behavior you would like your children to exhibit.

• Give children choices

When possible give your kids opportunities to make decisions on issues that effect them. This is respectful, encourages independence, and shows you have trust in them.

Your children are more likely to cooperate when they have had a say in the decision-making.

• Send clear messages about your expectations

• Establish clear rules

Know that it is in your children’s best interest to have clear rules that are consistently enforced with persistence, love, and warmth.

• Use praise

Praise your children for positive behavior that you would like to see repeated: “Catch them being good.”

• Plan ahead

To avoid problems, anticipate situations that might be difficult for your children. Prepare them for such times.

• Follow through with discipline and consequences

• Be consistent

Also allow for sufficient flexibility to accommodate specific situations and your unique child.

Summary of Three Parenting Styles

| Too Much Nurture (Permissive Style) |

Balance of Nurture/Structure (Assertive Style) |

Too Much Structure (Aggressive Style) |

| Evades |

Persists |

Blows up |

| Begs |

Listens to other’s point |

Has power struggles |

| “Makes do” |

Gives brief reasons |

Accuses |

| Acts flustered |

Reveals honest feelings |

Endlessly argues |

| Is unclear |

Politely refuses |

Discredits other’s ideas |

| Is a martyr |

Empathizes |

Tricks, teases, humiliates |

| Worries about popularity |

Carries out reasonable consequences |

Gives harsh punishment |

| Fears upsetting the child |

Accepts need to assert |

Rigid enforcement of rules |

| Blames self |

No blame |

Blames child |

| Inconsistent information about expectations |

Clear, direct requests |

Withholds information about expectations |

| Chaos in physical and emotional environment |

Rules are flexible and change as children grow |

Litany of strict rules |

There are three main parenting styles that are most commonly used.

There are three main parenting styles that are most commonly used.